The surprise attack on Pearl Harbor leads the United States to enter World War II. Necessity makes ideological foes into allies. The United States and the Soviet Union fight on the same side, but their leaders remain suspicious of each other.

Allies

1941–1945- March 5, 1943

Golden Gate Quartet, “Stalin Wasn't Stallin’”

The Cold War began in the aftermath of World War II. But go back a few years, to the wartime Soviet-American alliance, and you’ll find a Bizarro alternate universe in which America is stoked for all things Josef Stalin. Few pop-culture curios define this brief era better than “Stalin Wasn’t Stallin’,” the notorious (and catchy) pro-Soviet single put out by long-running gospel group The Golden Gate Quartet.

- May 22, 1943

Mission To Moscow

When it came to selling the American people on the alliance between the United States and the U.S.S.R., Hollywood studios led the charge, releasing a succession of pro-Soviet films, including The North Star (1943), Three Russian Girls (1943), and Song Of Russia (1944). None, however, would achieve the notoriety of Mission To Moscow, Michael Curtiz’s demented follow-up to Casablanca. Alternately stultifying and jaw-dropping, it even goes so far as to explain away Stalin’s 1930s show trials: It turns out the accused were all foreign saboteurs!

Tension

1945–1949In the aftermath of World War II, the disagreements over the future of Europe emerge between the Allies. The CIA is formed. The Eastern Bloc coalesces, consisting of the Soviet Union, its Communist satellite states, and newly created Yugoslavia. The first proxy wars are fought. A Soviet-backed coup d'état leads to a Communist takeover of Czechoslovakia. The House Un-American Activities Committee holds hearings on the extent of Communist influence in Hollywood. The occupied zones of Germany officially become different states, and the USSR tests its first nuclear weapon.

- September 19, 1947

Secret Agent

Just days after the surrender of Japan, an embassy clerk defected in Canada, revealing the extent of Soviet spy operations in the West for the first time. Within a couple of years, paranoia about Communist infiltration and influence took hold in America. Before long came Boris Barnet’s box-office hit Secret Agent, the first Soviet spy film. With its Third Reich setting, Secret Agent provided the template for subsequent popular depictions of heroic Communist spies. Soviet films would almost never directly portray the Cold War, preferring the backdrops of the Russian Civil War and World War II.

- March 8, 1948

The Russian Question

As relations between the U.S.S.R. and its Western allies grew antagonistic, the Soviet film industry began a push to produce movies that painted American democracy as corrupt and hypocritical—many of them set in the United States. Mikhail Romm’s drama The Russian Question was the most sophisticated of these, in part because it was the only Stalinist movie to present a convincing depiction of America, modeled on the Hollywood movies of the time. Along with Secret Agent, it points to one of the defining imbalances of Cold War media: with a few exceptions (almost all of them made under Stalin), the only Soviet films to feature American villains also had American heroes.

- June 8, 1949

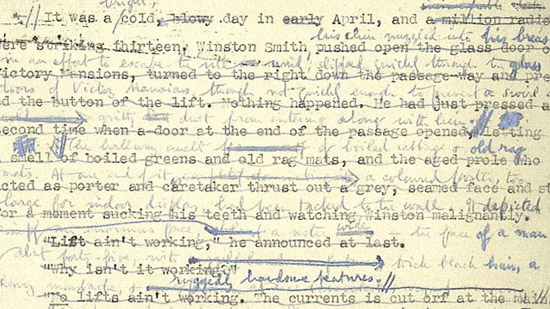

Nineteen Eighty-Four

The definitive dystopian novel, George Orwell’s classic is set in a totalitarian future England where reality is controlled through censorship and surveillance. An anti-authoritarian, anti-Soviet socialist, Orwell inadvertently ended up influencing the West’s own propaganda efforts and shaped much of the Cold War’s anti-socialist imagery. By the time 1984 actually came around, his novel’s imagery and language (“Big Brother is watching you”) had been co-opted to the point that they could be used in an advertising campaign that told consumers to break free by buying Apple products.

- 1949

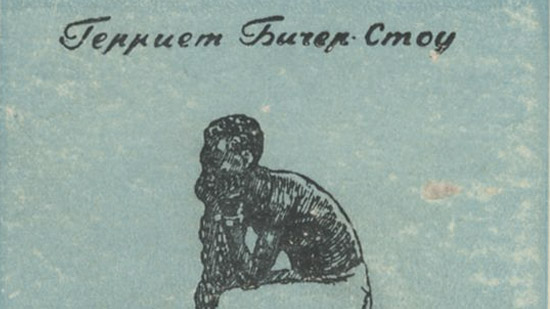

First Soviet edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin

By the time the Cold War came to end, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s abolitionist novel was arguably better known to Soviet readers than to Americans. Beginning with the new Russian translation published in 1949, the book went through a whopping 59 editions in the Soviet Union. It fed into the U.S.S.R.’s fascination with slavery, civil rights, and, later, African independence, all of which would figure prominently in its propaganda efforts at the height of the Cold War, putting the Soviets on the right side of history, though often for the wrong reasons.

Red scares, nuclear fears

1950–1956The United States and the Soviet Union enter a proxy war in Korea, which ends with the creation of separate states, North and South. The CIA plots to topple foreign governments, beginning with Iran. Stalin dies and is replaced by Nikita Khrushchev, who introduces liberal policies within the Soviet Union but is more openly antagonistic in foreign policy. The KGB is formed. The Soviet Union invades Hungary to suppress a popular uprising.

- 1951

Jackie Doll And His Pickled Peppers, “When They Drop The Atomic Bomb”

Country and hillbilly musicians put out scores of Korean War songs in the early 1950s, ranging from the underappreciated Jimmie Osborne’s somewhat premature “Thank You God For Victory In Korea” to the jingoistic “When They Drop The Atomic Bomb,” recorded by the mysterious Jackie Doll. Gleeful and gruesome, the song imagines what will happen to the no-good Communists when America finally nukes them for dragging “our boys” into a proxy war on the Korean peninsula.

- January 1952

Duck And Cover

Amid growing concerns about Soviet atomic testing and the possibility of global nuclear war, American schoolchildren were inundated with instructional scare films, the most famous being the U.S. Federal Civil Defense Administration’s Duck And Cover. In this film, a cartoon turtle named Bert demonstrates what to do in the event of nuclear attack—namely, hit the ground under nearby shelter. Though mostly remembered as kitsch, movies like Duck And Cover serve as reminders of how much the possibility of doomsday was ingrained into the public consciousness in the early decades of the Cold War.

- 1955

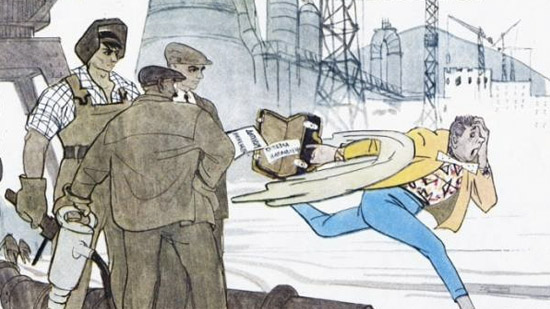

Krokodil takes on the stilyagi

While America was stricken with fears of Communist takeover and nuclear war, the Eastern Bloc mostly fretted about itself. The death of Stalin in 1953 had ushered in a brief period of cultural liberalization and the promise of prosperity. The long-running humor magazine Krokodil held an important place in the pop culture of the U.S.S.R., mixing digs at the West with jabs at Soviet life that were safely within the party line. In the mid-1950s, it began a less-than-subtle campaign of ridicule against the stilyagi, an emerging youth subculture known for its outrageous fashion sense and taste for Western music, much of it distributed through bootleg records made out of old x-ray films. As a notorious propaganda poster of the era declared, “Today he dances to jazz—tomorrow he will sell his homeland!”

- February 5, 1956

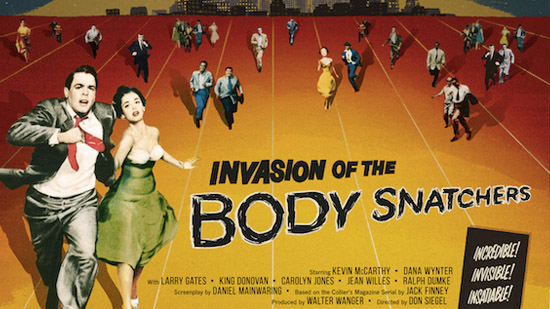

Invasion Of The Body Snatchers

The era of the drive-in B-movie was something of a golden age for anxious sci-fi allegories. The Thing From Another World (1951) was the first classic of the genre, with Don Siegel’s iconic Invasion Of The Body Snatchers being its finest example. The story of a small town whose residents are being replaced with duplicate “pod people,” Invasion can be interpreted as either a reaction against the anti-Communist scaremongering of the time or an expression of fears about Commie subversion. The two interpretations aren’t mutually exclusive. Body Snatchers’ central metaphor reflects the atmosphere of paranoia that pervaded American life in the post-McCarthy years: One could fear both a Soviet takeover and the irrational actions your fellow countrymen were taking to prevent it.

- 1956

Vladimir Troshin, “Moscow Nights”

The Russian title of the Soviet Union’s most famous pop song, “Podmoskovnye Vechera,” doesn’t refer to nights or the city; a more accurate translation would be “Evenings Outside Moscow.” It is a sentimental ode to the dacha, the country house that signified middle class comfort in Soviet life. The Cold War’s biggest impact on American pop culture at the time was a mix of fear and fascination, but in the Soviet Union, pop culture reflected a compulsion to project prosperity and stability.

The Space Race and escalation

1957–1960The Soviets launch the first artificial satellite into orbit. The Cuban Revolution gives the Soviet Union an ally close to American waters.

- 1957

Andromeda

The Soviet Union’s identity rested in part on the promise of the future, given credibility by its early successes in space. Arriving just as the Space Race was getting underway, Ivan Yefremov’s vision of the interstellar deep future was a milestone in the development of the Soviet science fiction novel. While popular American sci-fi made allegories of the Soviet threat, the Soviet sci-fi writers who followed in Yefremov’s footsteps—most notably the Strugatsky brothers—used the fantastic and futuristic as a way to phrase social criticism, moving beyond Andromeda’s didactic, utopian Communism to examine human fallibility.

- 1957

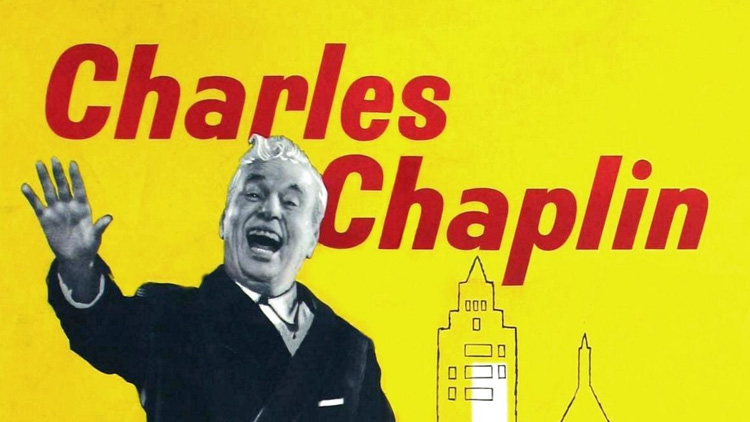

A King In New York

Still blacklisted in the United States, an exiled Charlie Chaplin tackled the Cold War in his final starring role. Chaplin’s deposed monarch travels to Manhattan to promote atomic power, only to find commercialism, TV, and anti-Communist scaremongering. It’s a world where people are sold all kinds of crap that keeps them from thinking, and technology isn’t being used to build a new world but to distract people from the current one. As mawkish and heavy-handed as it is unsparing in its assessment of American mores in the age of rock ’n’ roll, A King In New York stands as one of the most unique political artistic statements of the 1950s, despite its flaws. Although it was a box-office success in Europe, King would not be distributed stateside until 1973.

- 1958

Jerry Engler And The Four Ekkos, “Sputnik (Satellite Girl)”

The Soviet Union led the Space Race early on, as the country put the first artificial satellite in orbit, followed by the first animal, and then the first man. At the time, the secretive Soviet space program captivated the American public imagination, inspiring a whole subgenre of novelty songs, best exemplified by Jerry Engler’s rockabilly favorite, “Sputnik (Satellite Girl),” and by Louis Prima’s infectious “Beep Beep” (1957).

- October 23, 1958

Boris Pasternak wins the Nobel Prize

A Russian writer winning the highest honor in literature might seem like a triumph for the Soviet Union, but it brought only denunciations and accusations that smacked of the Stalin years. Boris Pasternak—a tremendously influential poet, writer, and translator who had long been in serious consideration for the Nobel Prize in Literature—had become an unwitting pawn of the CIA because of his dissident views. A trove of documents declassified in 2014 confirmed what had long been suspected: The CIA had undertaken an elaborate campaign to ensure Pasternak’s win and had printed the first Russian edition of his banned novel, Doctor Zhivago—later to be made into one of the highest-grossing films of the 1960s—all in an effort to publicly embarrass the Soviets.

Crises and absurdity

1961–1969The CIA-backed Bay Of Pigs invasion fails to overthrow the Cuban government. The Berlin Wall is built to separate East and West Berlin. The Soviets sever relations with China. The Cuban Missile Crisis brings the world to the brink of nuclear annihilation. A hotline is installed between the Pentagon and the Kremlin. The United States enters the Vietnam War amid a period of changing social values. Anti-Communist death squads kill as many as 3 million people in Indonesia. The Soviets crush another popular uprising, this time in Czechoslovakia.

- January 1961

Spy Vs. Spy debuts

A dominant geopolitical principle of the Cold War was “mutually assured destruction”—in other words, if you blow us up, we’ll blow you up too. The MAD world’s bottomless suspicion was lampooned in Mad magazine with Spy Vs. Spy, a comic strip in which two spies endlessly plot to maim and murder each other, and the more outlandishly paranoid spy always wins. Fittingly, the strip was created by Antonio Prohías, a cartoonist who fled Cuba in 1960 after Fidel Castro accused him of spying for the CIA.

- 1961

John Le Carré introduces George Smiley

John Le Carré’s debut novel, Call For The Dead, introduced George Smiley, who would appear in the intelligence-officer-turned-novelist’s most famous works, including The Spy Who Came In From The Cold and Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. An unglamorous observer and manipulator of human weakness, Smiley would come to personify the moral ambiguity of the Cold War at its coldest, when East and West seemed to be locked in a shadowy chess game that had little to do with ideals.

- November 1961

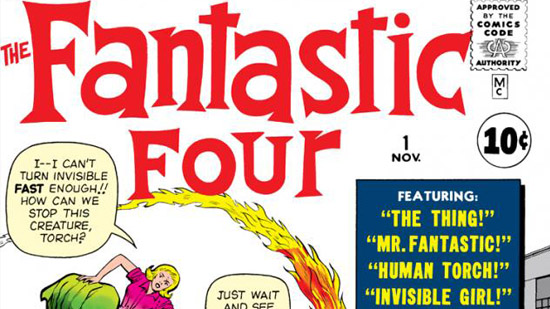

The Fantastic Four #1

As the popular depictions of the Cold War were about to shift toward the absurdist and ambiguous, in came Jack Kirby and Stan Lee’s iconic superhero team, figures of Space Race derring-do who were pitted (beginning with The Fantastic Four #5) against Central European dictator Victor Von Doom. It’s been said that the Fantastic Four are inseparable from their Cold War origins, but even in 1961, they represented an era of national ideals and scientific wonder that was soon to vanish.

- October 24, 1962

The Manchurian Candidate

John Frankenheimer’s classic thriller is as suspenseful as it is deeply, uniquely strange, envisioning the Cold War as a dream state, full of bizarre moments and creepy subtexts. It stokes the most irrational fears of Commie infiltration, only to use them as a corrosive. Released at the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis, The Manchurian Candidate captured a moment when the paranoia and nail-biting tension of the Cold War had been become so commonplace that it seemed like a key to the subconscious.

- January 29, 1964

Dr. Strangelove Or: How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Love The Bomb

"Gentlemen, you can't fight in here! This is the War Room!" Stanley Kubrick’s savage comic masterpiece may be the defining film of the Cold War, depicting a world being steered toward oblivion by insane jingoists, ineffectual leaders, sexual anxieties, and (literal) Nazi reflexes. A few years earlier, the idea of an American studio producing a movie like Dr. Strangelove would have been unimaginable. In the turmoil of the 1960s, it was a hit, leaving an indelible mark on the public consciousness.

- 1964

I Am Cuba

Filmed just months after the Cuban Missile Crisis, Mikhail Kalatozov’s breathtaking, decadent ode to Cuba was the direct result of the U.S.S.R.’s push to promote its emerging ideological allies in the Western Hemisphere, made with inventive camerawork and special infrared film supplied by the Soviet military. It might not have been the propaganda travelogue the Soviets hoped for, but its influence and stature has grown since the conflict that produced it began to fade away.

- March 23, 1967

Star Trek introduces Klingons

Star Trek’s vision of a human future unified by ideals was in part a reaction against the Cold War, and the franchise’s first incarnation is full of allegories for the conflict. Though they would eventually develop a culture of their own, the Klingons were first introduced as transparent stand-ins for the popular image of the Soviet Union: totalitarian, scheming, and stuck in a diplomatic deadlock with the United Federation Of Planets.

- January 8, 1969

Mr. Freedom

Photographer and filmmaker William Klein came to France with the U.S. Army in the aftermath of World War II and never went back. His screaming slam-bang satire Mr. Freedom is the kind of anti-imperialist, anti-consumerist film only an American expat could make, imagining the U.S. of A as a psychopathic superhero and the Soviet Union as a man in an inflatable suit. It is as irreverent as it was deeply angry about the absurd grandstanding it sees as the greatest threat to the world. This is what the Cold War looked like from the sidelines.

Détente

1970–1979The two sides of the Cold War become more cooperative, participating in joint summits and accords, but continue to fight each other in proxy wars. The Watergate scandal shifts the locus of American paranoia toward home. A CIA-backed coup turns Chile into a dictatorship, and the United States supports anti-leftist state terror campaigns in Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia and Brazil. In the last days of 1979, the Soviet invade Afghanistan, ending the détente era.

- June 27, 1971

Tatort vs. Polizeiruf 110

Germany’s two long-running, storied police procedural shows have their origins in the East-West divide that split the country into two states during the Cold War. The more character-driven Tatort—produced under a model in which regional stations contributed 90-minute episodes individually, creating a structure akin to an anthology series—debuted in West Germany in 1970. The East, never first but always eager to compete, introduced its own version, Polizeiruf 110, less than a year later; initially, it focused on less violent crimes than its Western counterpart. Over a quarter-century after the reunification of Germany, both are still on the air, distinguished mostly by their origins.

- April 1972

Pepsi enters the Soviet market

As the first available American product, Pepsi became an emblem of easing relations between the two sides of the Cold War for Soviet consumers, and, eventually, of perestroika. America’s second-favorite cola enjoyed an unrivaled iconic status in the Soviet Union, later becoming an object of nostalgia.

- 1973

Dannon’s “In Soviet Georgia” campaign

“In Soviet Georgia, where they eat a lot of yogurt, a lot of people live past 100." Though the (comparatively) relaxed atmosphere of the early 1970s is best remembered for introducing Western consumer goods into the Eastern Bloc, the shift went both ways. Immensely successful, Dannon’s commercials were shot in the mountains of the Soviet republic of Georgia—the first American ads to be filmed behind the Iron Curtain.

- 1975

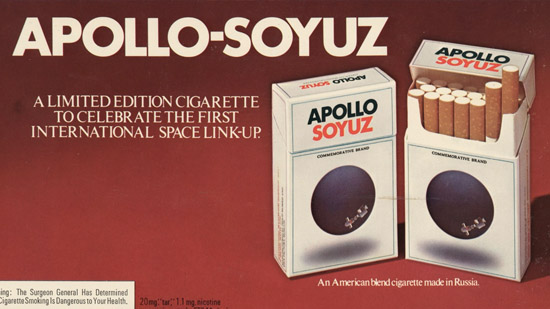

Soyuz-Apollo cigarettes

The Soviet Union was a nation of chain smokers. The state-run tobacco industry could slap just about anything it wanted on a pack, and often did. (There were two different Soviet brands with hydrofoil ferries for logos.) The packs became a form of pop culture in themselves. To commemorate the first joint Soviet-American spaceflight, the Soviet Union joined forces with Philip Morris to produce a brand called Soyuz-Apollo, sold as “Apollo-Soyuz” in the United States. Still widely available in Russia, they commemorate a brief promise of collaboration in the midst of the Cold War.

- May 25, 1977

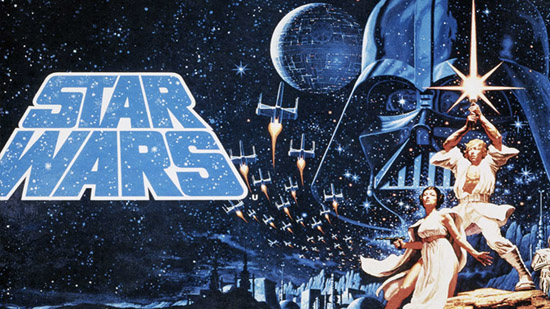

Star Wars

An effortless pastiche of space opera, pulp serial, World War II flick, and samurai movie, the original Star Wars (which acquired the subtitle A New Hope in 1981) is anything but political. Yet its immense popularity was politicized before long, becoming a go-to reference point for an America that was soon to slide back into the Cold War. While the film hit theaters during the Jimmy Carter administration, it came to define the ramped-up antagonism of the Reagan era—from the proposed SDI missile defense system that would protect the United States from the decades-old threat of Soviet nukes (nicknamed “Star Wars”) to the president’s use of “evil empire” to describe to the visibly collapsing U.S.S.R.

- September 23, 1977

David Bowie, “Heroes”

By the 1970s, the image of a Germany split into East and West by the Cold War had become intractable, ingrained into the global consciousness to the point that the Berlin Wall became a shared metaphor for division and struggle, inspiring one of David Bowie’s greatest and most enduring songs—and one of his best albums.

The second Cold War

1980–1985The Solidarity movement begins in Poland. The United States leads a boycott of the 1980 Moscow Summer Olympics; the Soviets respond by leading a boycott of the 1984 Los Angeles Summer Olympics. Ronald Reagan is elected on an anti-détente platform, and he brings to the White House a new antagonism toward the U.S.S.R. Mikhail Gorbachev becomes the leader of the Soviet Union, ushering in new policies of glasnost (“openness”) and perestroika (“restructuring”).

- 1980

Missile Command

By the 1980s, the specter of nuclear annihilation was so familiar that its shock value had worn off. What was once the stuff of existential angst now served as the premise of an Atari arcade game, Missile Command. Players control a pixelated facsimile of the NORAD command center as they seek to save cities from a hail of ballistic missiles using a few puny anti-missile batteries. The quixotic notion of defending against a nuclear attack was in the air: A few years after Missile Command’s debut, Ronald Reagan proposed a fanciful space-based defense system—the aforementioned missile shield that the media deemed “Star Wars.” The video game was more realistic.

- August 10, 1984

Red Dawn

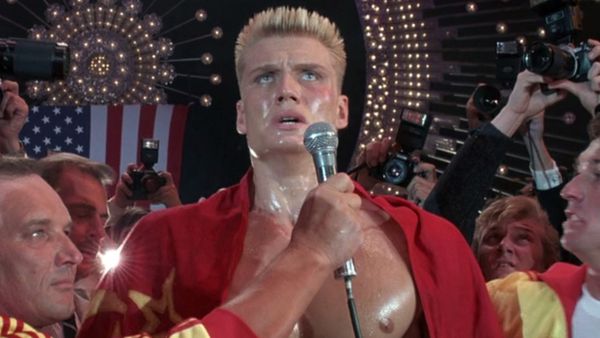

John Milius’ loony survivalist fantasy pitted can-do American teenagers against a Communist invasion. It was among the best examples from the Reagan-era golden age of the Soviet villain, along with the Sylvester Stallone vehicles Rocky IV and Rambo III. The Hollywood of the 1950s feared Soviet manipulation and indoctrination while 1980s American media fetishized Soviet might—ironic given that the Eastern Bloc was rapidly fracturing, with the Soviet Union itself stuck in the unwinnable, destructive Soviet-Afghan War.

- 1985

Wendy’s Soviet fashion show campaign

Totalitarian drabness was a source of fear in the early years of the Cold War, but by the 1980s, it had become a joke. Like Apple’s Nineteen Eighty-Four-inspired Super Bowl ad, which ran the year before, Wendy’s commercials in 1985 focused on the idea of consumer choice, though with a much lighter tone. The fast-food chain went through a number of different campaigns in the second half of the 1980s, occasionally returning to the Soviet theme.

The end

1986–1991Gorbachev’s policies liberalize the Soviet Union but also prove economically disastrous, speeding its collapse. The Reagan administration secretly sells arms to Iran in order to fund right-wing militias in Nicaragua. The Berlin Wall is torn down. East and West Germany are reunited. The Soviet Union’s satellite states overthrow their Communist governments, while its member republics declare independence. Yugoslavia fractures, plunging the region into a series of ethnic wars. Lt. Col. Vladimir Putin resigns from the KGB to pursue a political career.

- 1988

Akvarium, “Train On Fire”

“And the men who shot our fathers / are making plans for our kids.” If the Soviet Union had an end credits song, it was “Train On Fire” (“Poezd V Ogne”), by the bewilderingly eclectic Russian rock group Akvarium. Though front man Boris Grebenshikov—soon to make a disastrous crossover attempt in the United States—claimed that the lyrics were apolitical, the song is rife with metaphors for the failure and approaching collapse of the Soviet Union, beginning with the vivid image of the title. Most Americans had spent their whole lives worrying about what the Eastern Bloc might do to the world, only to watch it break up because of its own unsustainability.

- 1990–91

Wolf Blitzer’s Gulf War coverage

CNN’s Wolf Blitzer was born in 1948, in Allied-occupied Germany, to Jewish parents who had fled Poland. So his life is rooted in the beginnings of the Cold War—but his fame is rooted in its end. In 1990, as CNN’s military affairs correspondent, Blitzer rose to prominence with reports from the Pentagon on the unfolding Gulf War, the United States’ first post-Cold War international conflict. He was part of a new media operation that cast warfare less as a grand geopolitical struggle than as a postmodern, real-time televisual spectacle dominated by the world’s sole remaining superpower.

Can't see comments?